Another excerpt of a longer fictional piece I am working on — more here and here.

*********

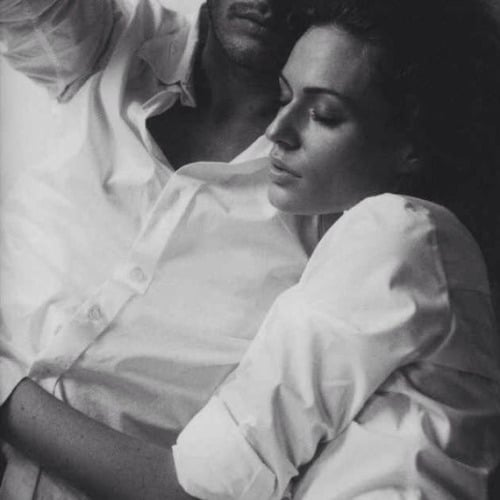

Companion music for this segment: Celeste’s heart-rending “Strange.”

*********

I did catch a glimpse Powell once in the four years we were “on a break,” and it was the day I graduated from the University of Virginia. Grounds were flooded with students, my parents were in town, and Buck — by some stroke of good fortune returned from his first deployment to Iraq — arrived at my door at 8:45 in the morning in full military regalia with a bouquet of white roses. My friends and I took pictures on the south side of Mad Bowl, a band of girls in caps and gowns, bare ankles and white smiles, arms threaded around one another, while throngs of classmates I had never seen before and families from parts unknown roamed around my hometown of four years. Buck stood a few feet from our pearl-dotted menagerie, holding my camera at the ready, smiling politely in anticipation. I clutched Charlotte’s hand and she smiled and squeezed back, misinterpreting the gesture as overblown excitement. But it was the dizzying crowd, the sickly pomp, the sudden apparition of Buck after nearly three months of not seeing him and the way he ducked beneath door frames and sprawled out on sofas and gestured to me with a half-energetic open hand: “C’mere, Linie.” I had cried into his uniform at the door that morning, and he had laughed when I’d pulled away and said, “Is this a funeral or a graduation?” I’d hated his glib invocation of death, whose specter already materialized too frequently in the habitual clenching of his jaw and the way he instinctually performed a scan of any room he entered, alert to danger. Even standing on the south side of Mad Bowl, erect and polished, with that decorous and dimpled smile on his face, I watched as clouds would gather and dissipate in momentary returns to Fallujah, his neck stiffening against the jostling of a rowdy group of boys, his eyes involuntarily tracking the figure sprinting across the field.

And so his casual dies irae at my doorstep sent my world further askance.

I was crossing Emmet with the plan of cutting up the outer flank of the academic village rather than plowing through the clusters of stagnant bystanders on the Lawn, but just as I was about to turn onto the brick-paved fork that would lead me past the Chapel,

it was him —

He was leaning against a lamp post, as unperturbed as ever, and just by the drape of his body, the confidence of his arc, I knew it was him before I even took in the low-slung khaki pants and immaculate white oxford and the sandy hair still as boyish as it had been two years prior. A flash, a lightening bolt, a prickly feeling of hot and cold spiraling from my stomach outward. I stopped in my tracks with the plan of reversing to the opposite side of the Lawn. But he turned and, rather than registering surprise or hurt or embarrassment, he just stared straight at me, and I could see the muscles in his jaw moving, and the steely set of his eyes was illegible. I was electrified by the constancy of his gaze. Was it longing, or anger, or malice? I blinked, and there he was, knee deep in water froth in his brown waders, the curve of his line over his head, and everything — the trickle-trackle of the stream, the still of the air, the galloop! sound his boots made in the water — reduced to the exquisite joy of his hand at my waist when he’d arrived, freshly showered, his still-wet hair combed out of his eyes, at my sorority formal that evening when I hadn’t expected him. I blinked again and a tangle of long limbs and a flash of blond hair interrupted my view, and it was Sumner with her arms around his neck, and though I had the split-second thought that it might be better if I could hang there — let him see me see them together, as if to prove some point I’d been meticulously constructing in my silence for the last few years — I turned and sprinted in the other direction, losing Buck, and the cloudy promise — or was it peril? — of Powell, in my wake.

How could I have known that he was there, that morning, to quietly accept the belated conferral of a second degree in an obscure form of engineering management he had earned alongside his B.S. in Business? That he had no relationship with Sumner? That he had crossed paths with her the night prior at The Biltmore, shrugging politically when she had asked for a pour from the $2 pitcher of beer of Nattie Lite he and his friend George were sharing? That he had peeled her long arms from around his neck and politely shifted away, scanning the crowd for my now-ghosted form, just seconds after her unsolicited hug?

I sprinted through the day, tugging my wrist out of Buck’s straining reach three, four, five times, before he sat back on his heels. I’d not realized I needed the contrepoids of his outstretched hand to remain standing, and so that damned dinner at Farmington Country Club, generously arranged by my parents, loomed ill-starred ahead. Buck was out of his mind with booze before the entrees had been served, his voice too-loud, liquored legato. I had steered him out of the dining room and hissed something exasperated his way, and the words he said after —

The spite, the anguish. I could see I had been a thin wraith of promise against forces enormous and eternal, and I felt sick with guilt.

I don’t know how we maneuvered our way through the rest of that evening or the stand-off that followed, but later that night, I crept out of my bed and laid next to him on the floor, where he had stubbornly insisted on sleeping, and I pressed my forehead against the slab of his back. He did nothing to register me, but I had sensed his eyes open in alarm at the shift of my sheets and the pad of my toes on the floor.

“Look, Linie,” he whispered. And on the underside of his arm, the same arm branded with the insignia of his family ranch, was a small black tattoo:

CAROLINE

I gasped at its permanence and desecration. Only the way he looked at me — as if he was proud — reformed my chastising thoughts, and I instead put my arms around his neck.

“I love you,” I whispered, and it was the only possible thing I could have said, as it was true, but it was also a diversion, and also what he desperately needed to hear–not so much as my boyfriend but as the boy who fought in Fallujah against the wishes of his Daddy and Pop Pop and, I knew, just wanted to belong to someone, to something.

It was the mark of my name on his body that would sit unwell with me for the rest of my life: the unwanted inscription of myself on a boy who needed me far more than I needed him. We would separate, our silhouettes gradually winnowing down to the slenderest mirages of our former selves. I would forget that he sang Aerosmith at top decibel in the shower, and preferred Pepsi to Coke, and could not stand the show “Friends.” That he was unfazed by spiders, critters, and rodents, but cagey around snakes — and there were a lot of them on his family’s ranch. That he wore the same pair of unwashed Levis for months on end, that he wrote in small capital letters, that he didn’t really hold me so much as throw his arm loosely around my neck when we were sitting together on the couch. But I would wake in torturous realization that somewhere, in some part of Texas, there was a man who bore not only the scars of war but the permanent black of my name.

P.S. Memoir-style essays on falling in love at UVA here and here and here.

P.P.S. And a love letter to Mr. Magpie on our ten year wedding anniversary.